this too shall pass

We don't open for visitors until two, they said.

So I wait.

Counting the minutes in the long corridor framed by windows like a cloistered passage, dappled light falling onto the old Linoleum floor through tinted glass in uniform increments.

Others wait too; checking their watches, their phones, swallowing hard against the immensity of what's to come. For the man stood beside me, his eyes so heavy and tired, it triggered an anxious dance. Rhythmically shifting his weight from one foot to the other; a silent shuffle soundtracked by the clatter of porters and the mundanity of passing visitors.

For us, waiting to enter the solemnity of the ward, there is no chat, no small talk, no smiles. Just the impatient beat of our hearts

The future does not exist beyond these walls.

There is only now, only the corridor, only the waiting.

At two, we file in silently.

Our anxious chorus removed our coats, hanging them on worn metal pegs, shedding our outside skins. We take our turn to wash our hands in the tiny sink, scrubbing away the germs in a miniature font of cleanliness; the ritual to allow us to cross the threshold. We dry our hands on blue paper towels. Each of us, in turn, realising our hands are shaking. A faint tremor of uncertainty and expectation, our bodies betraying us.

Your surgery took ten hours.

They removed so much.

They hollowed you out. Taking the core of you, the private geography of your body, repositioning what remained. But they also took the tumour and lymph nodes. The silent malignancy that survived the sustained attack from prescribed chemical and radioactive warfare. Weakened by it, but stubbornly refusing surrender, despite the onslaught.

The surgery went on far longer than they expected.

They needed four, separate surgical teams.

You lost so much blood.

Your body giving way under the knives and sutures, as if you were being unmade and remade all at once.

I kept ringing the hospital for an update, listening to that endless dial tone.

“Call again in an hour,” they said.

And when I did, “call again in an hour,” came their response. Time slowed to a crawl, it became thick and viscous, something to wade through. Each minute stretched thin as gauze.

When we were finally able to speak on the phone, as you came around in recovery, it sounded like we were talking between universes. The delay on the line insurmountable, our words traveling through deep space. Your mind, warped and distorted from the drugs, attempted to make sense of what I was asking, what I needed to tell you. That I love you with every fibre of my being. But few words came back, bent by morphine and trauma into something unrecognisable.

I pull the elastic straps over my head and lift the blue and white mask to cover my nose and mouth. My hot breath steaming my glasses, fogging the world.

A nurse buzzes me in.

The critical care ward is a square room, beds against the walls like watchmen standing vigil. In the centre, a nursing station that looks like a manager's desk in that call centre we used to work in years ago; the mundane machinery for the management of miracles. The nurses hum around the room, busy as worker bees tending to their helpless hive, moving with such practiced grace between the monitors, the computers and the resting bodies.

The lighting is dim here. The world outside has been softened to a barely a hush and brightness would be an unwelcome intrusion.

And there you are.

In the corner of the room, covered in wires and tubes, surrounded by monitoring equipment that beeps, chimes and buzzes. A drip feeds you with water, a drain carries it away; the ins and outs of staying alive, laid bare.

You look small, like a sleeping child, your body diminished by the violence it has endured.

The relief of seeing you, so fragile yet so resilient, expands in my chest like the first vital breath after resurfacing from deep water.

I rub your hand, your fingers dry as old paper. You stir and look at me, smiling through the fentanyl-laced fog. We barely speak, our eyes deciphering the code, reading each other in the language we've spoken for years.

It really is you.

The man in the next bed is a talker. He fills the silence with words, because silence is where his fear lives. A nurse fills a chipped and scratched beaker with water. “I hope it's gin and tonic,” he says. Again. The nurse musters a smile, kind but tired. She tells him to drink, that he's been through a lot.

He talks to avoid the caller on his internal other line. It is the caller that brought him here, the caller that waits in the pauses between his sentences.

Your physio arrives.

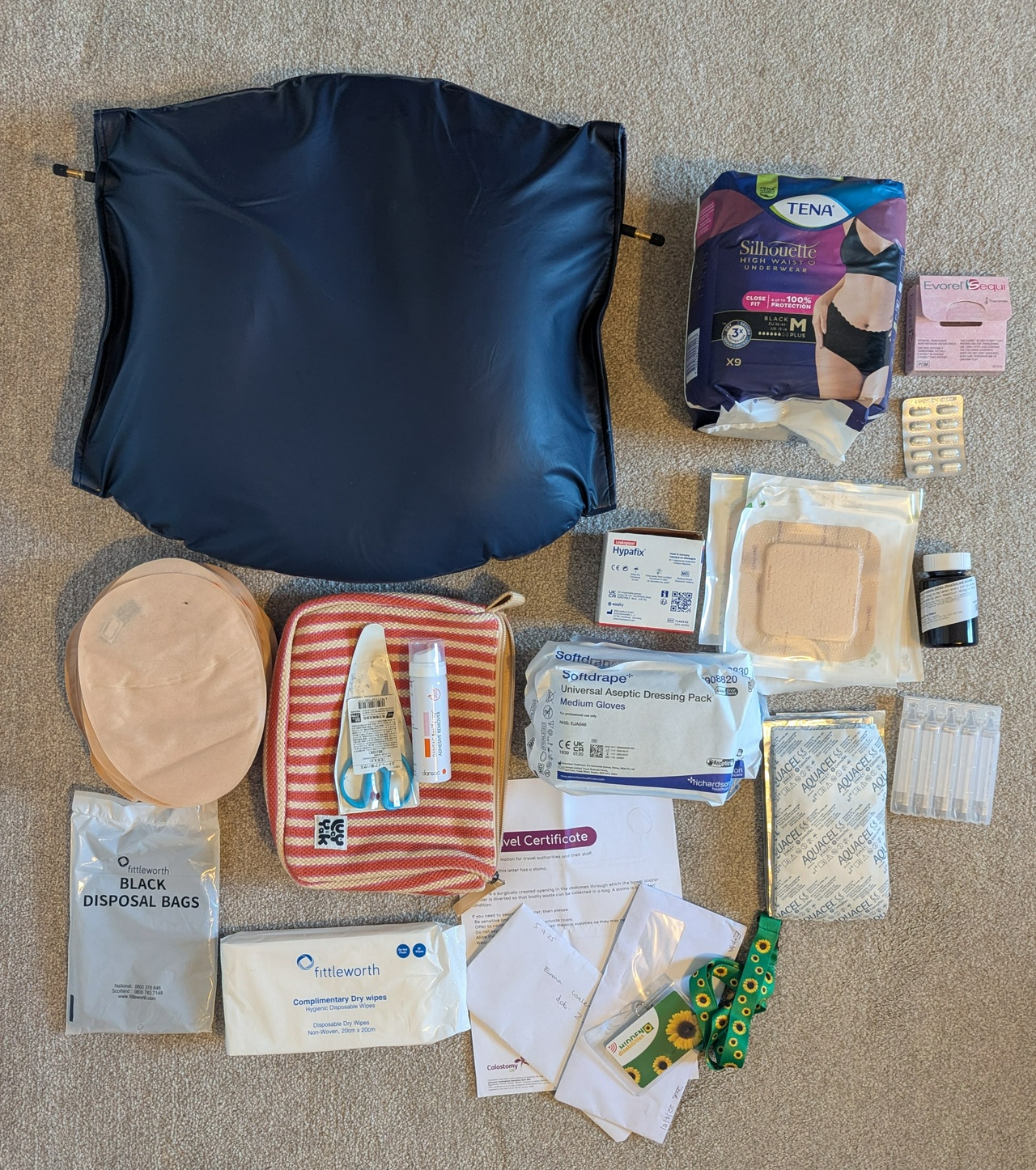

She wants to get you moving, less than a day after they took away so much. They help you to your feet, another nurse carrying a heavy shoulder bag of fabric covered equipment, its wires coming from your chest like the strings on a marionette. I carry bags of urine, bags of blood and liquids draining from your wounds; the very viscera of your survival.

You shuffle slowly around the quad of beds, like a slow motion Great Court Run at Trinity College, each step a Pyrrhic victory against the pain. It's an ultramarathon done in five minutes.

Exhausted by your efforts, they help you back into bed, sending chills through me as your face contorts with every turn and twitch.

I want to take this pain from you.

I want to carry it myself.

A woman comes in with a dog, leading him to a bedside already surrounded by weeping relatives, a gathering of witnesses.

“They allow pets?” you ask, your voice filled with wonder. “You could bring Sid to see me!”

I think they're saying goodbye, I reply, my voice breaking as I absorb the magnitude of the conclave. Love made truly visible only in the presence of the whole family. A curtain is closed.

This is not a moment for us. But for them.

The next day, everyone in and around the bay is gone, replaced by a elderly woman lost in a dreamless sleep; the players reset, the drama continuing.

I offer you water but you struggle to swallow, your lips chapped from hours without so much as a sip. Even drinking now requires negotiation with your body.

You're so tired, you tell me, in a voice barely above a whisper.

I hold your hand, and softly stroke your hair as you drift back to sleep.

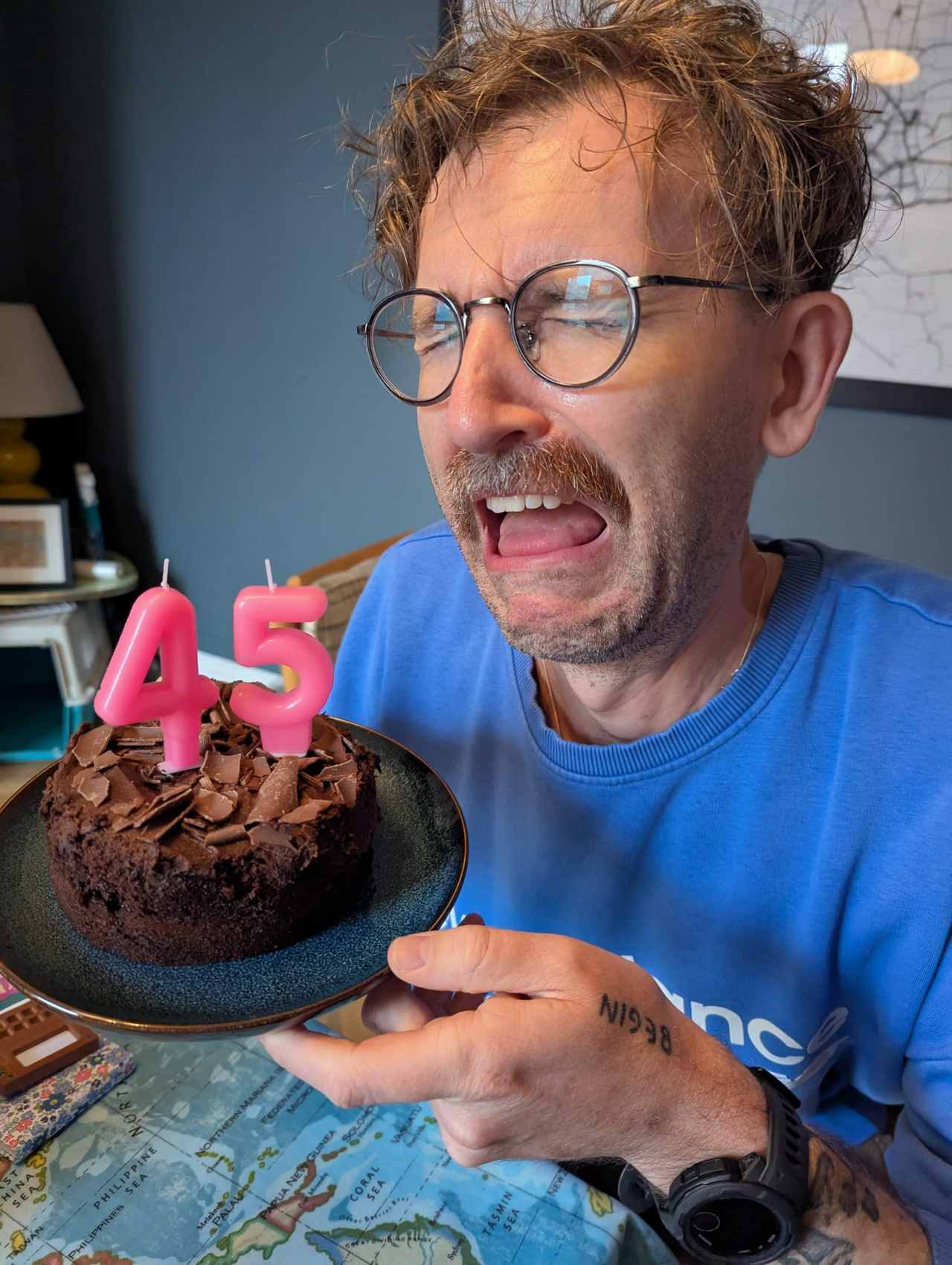

I bring our arms together, skin to skin, the contact we both crave. The words that were pushed into our skin just the week before, small black letters, speaking the wor

ds we are both unable to say: this too shall pass.

And I believe it.

I have to believe it.